How grief comes into our lives and making room for it.

By Gregg Snook M.A., NCC, LPC

So, recently I have had many conversations with people who have lost someone they loved. I find people rarely label the feelings that come from something changing or ending as “grief” unless it has something to do with someone’s death. It is reasonable to consider the connotation of grief as only applying to the death of someone who mattered to us, but I propose the following: grief is a feeling that occurs when our lives irreversibly change and we struggle to adjust to the cognitive, emotional, situational, and/or relational changes. I plan to write more about the different ways that grief enters our lives but today I wanted to focus primarily on how, when, and what we can do when grief comes to us.

Experience of grief.

Grief, as an emotion, can be one of the worst experiences of our lives. The turmoil, worry, confusion, sadness, anger, desperation, and hollow feeling that can result when someone we love passes away can be something that we fear with great trepidation. When it occurs, the overwhelming feeling often escapes the description of words. We express it in sleepless nights, tears, anxiety, fear, and sadness. First, I want to discuss why these feelings, intense and ominous, occur within us after we lose someone.

I like to ask people to reflect on this idea: grief exists on one side of a coin, on the other side is love. This idea is echoed in writers such as Kubler-Ross, Kessler, and Worden. The more intensely we love someone, the greater feeling of grief that results when they leave us. We live our lives with the experience of those we love and we feel it, in many ways, when they depart from our lives.

Grief as a gift we never wanted to receive.

I am sure the idea of grief as a gift is something that is contradictory and difficult. When we share our lives with people we love, they impact us. They change how we think, spend our time, and how we remember the time we spent with them. These impacts are kept by us in memories, idiosyncrasies, and many other ways. These impacts are part of what we miss when we lose them. The gift of grief is what we keep and how strongly we realize what we miss. Realizing that our lives have changed and the persistent experience of grief that occurs afterward is the reason why, once we receive the gift, we can never get rid of it.

Grief as a vase.

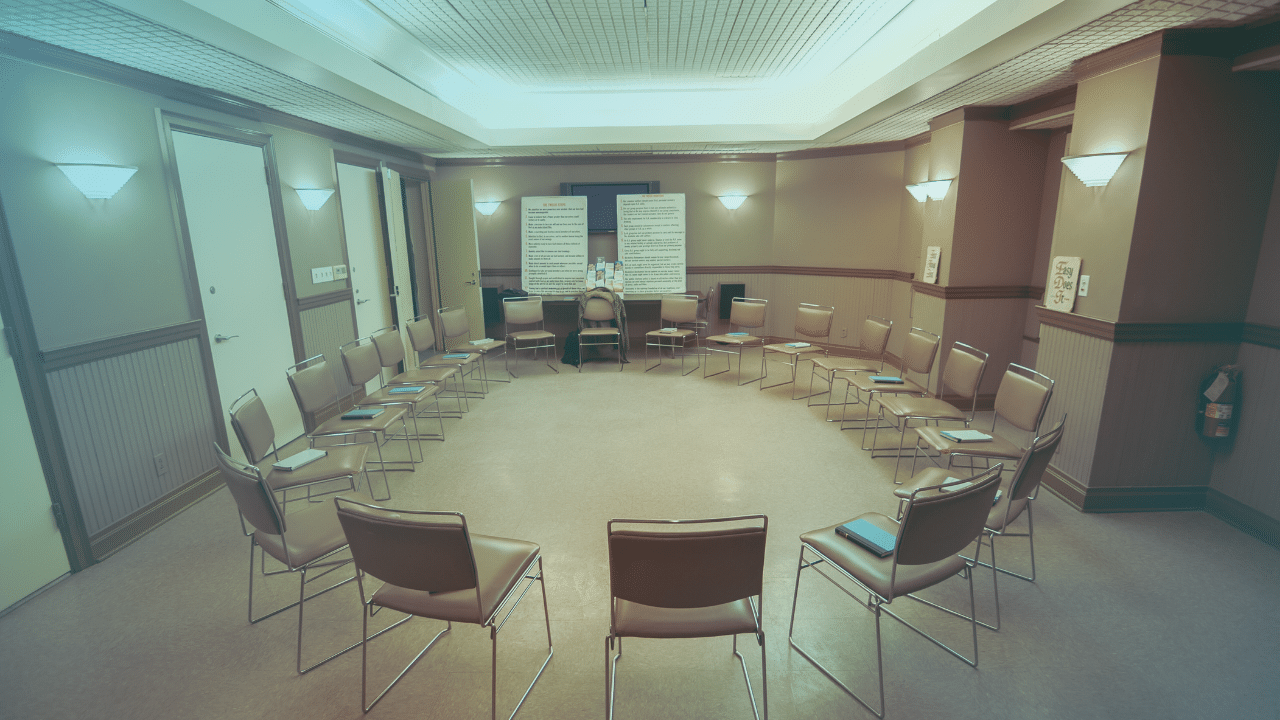

This is a metaphor I use with clients and support group members to explain how the feeling of grief never leaves us. I hear often that “time heals all wounds.” That one gets around more than requests for “Freebird.” Considering grief as wounds makes sense in how those affected are left with scars, but rather than the idea of “It goes away with time,” I like to remind people that in healing from grief, the feelings never go away; instead, they change.

The gift of grief is a result of the deep feelings of connection and love we had with the person we’ve lost. But this is a gift we never want to receive. Now to the metaphor. You receive a gift of a vase in the mail one day. You are unsure from where it came or from whom. Also, the vase in question is UGLY. I mean made by a blind person in a horrible mood ugly. It is lop-sided, has the worst color combinations, is disproportional, and has parts that break off, but it can withstand a long drop so it can never be thrown away. Which brings me to why it is a gift that we can not throw away or re-gift. This gift came to us as a result of all of our experiences with those whom we love and have left us. The vase would never have been delivered to us, in all its hideous glory, without first having such love for another person. The gift of the vase is something that represents all of the memories, feelings, hopes, dreams, laughs, and most of all love, that we shared with the person who passed away.

So, what do I do with this vase?

Well, we can’t get rid of it, we can’t smash it, and if we do it’ll still stay with us. Instead, I offer another way to cohabitate with this ugly, disruptive thing. Find out where it belongs. Move it around. Put a hat on it. Put some flowers in it. Collect rain water (tears) in it. Fill it with candy. Do whatever you have to do but do not ignore it. Grief does change as time goes on. The pain never ends but it changes over time. We can take the grief vase and put it on a mantel to observe for months. Then we can take a break and keep it with the holiday decorations. We can keep it in the basement. We can use it as a paperweight, doorstop, a pitcher, anything. We have to get to know it, understand it, and see where it fits into our lives. We will place it in areas that are difficult for us to navigate with it there. Tripping over a vase on your way out of the house will teach us it doesn’t belong there, it will get in the way.

The point of all of these metaphors is that it is a struggle to get used to the feeling of grief when we experience it. The HBO series Six Feet Under described, pretty well, how the average Americans’ approach to grief is very sterile. The main character recounts to someone in the first episode about how in America we clean up the process of a loved one passing and then disassociate from it in order to “maintain our composure.” In many other cultures and countries, death is a very intimate and emotional process of preparing the dead, the funeral rights, and then the aftermath. I, personally, am very fascinated and impressed by the Jewish tradition of sitting shiva. Shiva is a process of grieving in Judaism of observing a person’s death with great attention for a period of about seven days. During this period, the tradition involves sitting on hard chairs and fully experiencing the emotions of the loss. This experience can be shared by others as a way of fully processing what it means to us to lose someone we loved so greatly and meant so much. A full range of emotion, however, can be incredibly difficult, overwhelming, and taxing.

T.E.A.R Model.

William Worden is a psychologist who worked to develop the T.E.A.R. model to address grieving as a process. This is a model I use often when addressing grief issues with clients and it is more dynamic than the precursor work of Kubler-Ross (which has become more nuanced with time and was a major part of developing all grief work by starting the conversation). The T.E.A.R model suggests that there are four tasks of grieving in order to complete and regain equilibrium after experiencing a loss. The first task is working To accept the reality of the loss. This can be difficult, as we often experience times where the loss feels so great that we can’t “accept that they are gone.” The second task is Experiencing/addressing and working with/through the pain of the loss. This is how we get used to our vase and try out the most appropriate place to have it in our lives. The third task is Adjusting to a new environment formed from the loss of our loved one. The fourth and final task is find a new and meaningful connection with the deceased and Reinvest in the new reality.

The way I explain this to people is that the process of the tasks is like accepting the delivery of the vase, really seeing how ugly it is, figuring out where to put it, and remembering why we received it in the first place. The ugliness of the feelings of grief can, again, be seen as how much the person meant to us. As Kessler says, grief is the other side of love.

Addressing our grief is WORK. There is a lot of relief in having time to ourselves when we are faced with grief but this can also be met with how lonely it can feel when others in our support system “move on” and we feel left alone with a menacing feeling: grief. When we love someone, they impact our life. We experience the side of the coin that holds love and connection. When they leave us (through death, separation, or other things), we experience the other side of the coin: grief. We grieve as strongly as we love. We cannot have one without the other or we would never feel the impact of the loss. When we are faced with the experience of that emptiness, we experience grief and can choose to do things that make it meaningful for us. I will write more about the tasks later. In this article, I wanted to talk about the feelings that occur and what we do with the change that comes with loss. The first part is the feeling.

If you are a person who is suffering with a loss and are ready to explore your feelings of grief and loss, please reach out for help. This can be in the form of a support group, a trusted friend, a member of your faith community, or other supports.

Explore this article:

Explore Our Facilities

Drug and alcohol detox and residential treatment for addiction and mental health disorders

Outpatient treatment center for substance use disorder and mental health disorders

Outpatient treatment center for substance use disorder and co-occurring mental health disorders